The Road to VIS 2024 - Conference Talks 101

There is an art to orchestrating a successful talk session at any conference, including IEEE VIS. Whether you’re a session chair, speaker, or attendee, this blog post will help you make the most of your IEEE VIS experience, and to help others make the most of theirs.

For Session Chairs

Session chairs play a crucial role in ensuring the smooth flow of presentations and discussions during the VIS conference. Your responsibilities begin before the conference and continue to the end of your assigned session.

You should be communicating with your speakers even prior to the conference. Reach out to them well in advance, requesting a preprint PDF of their paper to familiarize yourself with their work if you cannot easily find it with a quick search online. While you don’t need to read the papers in depth, skimming them will help you generate potential questions and lead a more engaging discussion. Although you will hear from the VIS organizers which of the authors will actually be giving the talk, you should double check with the speaker to ensure that this information is still correct.

When you arrive at your designated room during the conference, introduce yourself to the student volunteer and A/V technician. Knowing who these individuals are will be invaluable if any technical issues arise during the session. Once your speakers start to arrive, take the time to learn the correct pronunciation of their name. Write it down phonetically so that you will be able to repeat it reliably in the heat of the moment. You should also make sure that they have all plugged in their computers and tested their setup.

Open the session by stating your name and affiliation. Give a (very brief) overview of the papers that will be presented, setting the stage for the audience. For example, you could say “Hi everyone, my name is X from Y, and I will be your session chair today. Our session has six exciting papers on the topic of Z. Let’s start with the first paper, which will be presented by W.”

Time management is one of your key responsibilities as a session chair. IEEE VIS is a large event with multiple parallel sessions, and many attendees like to “session hop” between talks. To facilitate this, it’s crucial to not just start and end your session on time, but also the individual talks in the session. You should probably work out the exact timing in advance. Consider using prepared signs (or slides) to keep speakers aware of their remaining time, such as “5 minutes left,” “2 minutes left,” and “Time’s up.” As session chair, you are responsible for leading the discussion during the Questions & Answers (Q&A) after each talk. Have your own questions ready in case the audience needs encouragement. Manage the length of the Q&A period appropriately, and be ready to politely cut off long-winded questions or answers. If there’s a line at the microphone and time is running short, you may need to respectfully inform waiting attendees that you’ve reached the end of the Q&A period.

As you wrap up the session, thank the speakers and attendees, and remind everyone of any upcoming events or announcements.

Summary of key things to remember:

- Communicate with speakers before the conference and familiarize yourself with their work;

- Learn how to pronounce each speakers’ name before the session begins;

- Manage time strictly, using visual cues to keep speakers on schedule; and

- Be prepared to lead the Q&A, having your own questions ready if needed.

For Speakers

As a speaker, your goal is to effectively communicate your research while respecting the time and attention of your audience. Thorough preparation is key to a successful presentation.

The VIS conference typically provides a speaker ready room where you can test your technology and rehearse your talk. Take advantage of this resource to ensure your laptop connections, audio, video, and any demos are working correctly. Practice your talk to make sure you can comfortably fit it within the allotted time. Note that you probably have to schedule a slot in the ready room, so plan in advance.

On the day of your presentation, arrive at the session room at least 15 minutes before it starts. Introduce yourself to the session chair and confirm the pronunciation of your name. And if you’re on the job market, let them know—they can announce it at the start of your talk, which is a great way to increase your visibility!

During your talk, be mindful of the time. Start and end your presentation on time, paying attention to any time-keeping signals from the session chair. Aim for the “Goldilocks length”—not too long, not too short, but just right.

During the Q&A session, keep your answers concise and to the point. If a question requires a lengthy discussion, offer to continue it after the session (this is also how you deal with a very technical and/or too specialized question). As your time slot comes to an end, be prepared to vacate the podium promptly for the next speaker. You can even begin packing up your equipment while answering final questions if necessary. After your talk, stay in the room to field additional questions and be open to continuing discussions during breaks or social events. One of the great benefits of in-person events is the chance to discuss your work with others at odd times during the event—make sure you take advantage of this! Summary of key things to remember:

- Arrive early to test your setup and meet the session chair;

- Adhere strictly to your allotted time; and

- Be prepared for the Q&A, offering to continue lengthy discussions after the session.

For Attendees

Attendees play a vital role in creating an engaging and respectful atmosphere. Please enter the room quietly if you’re joining a session in progress. If you’re planning to “session hop,” try to do so between talks to minimize disruptions.

Remember that questions, even if they are critical, show your appreciation for the speaker’s work. In other words, if you have a question, don’t hesitate to ask—it’s the best way to compliment the speaker. Do think through your question before you get to the microphone to ensure that it is concisely worded and relevant to the talk. If you find yourself starting with the infamous words “I have more of a comment than a question”, step away and save that comment for a later one-on-one discussion with the speaker after the session is over. When it’s your turn, start by stating your name and affiliation, then speak clearly into the microphone. Always use the provided microphone for accessibility reasons: “I’m loud” is not loud enough for people in the room who are deaf or hard of hearing, or those who are listening to a session remotely through a livestream or a recording.

Summary of key things to remember:

- Enter and exit rooms quietly, especially when “session hopping”; and

- Ask concise, relevant questions and always use the provided microphone.

Closing

By following these guidelines, we can all contribute to making IEEE VIS 2024 a successful and enriching experience. Whether you’re chairing a session, presenting your work, or attending talks, you have an important role to play in fostering a collaborative and insightful conference environment.

We look forward to seeing you all at IEEE VIS 2024 in a few short weeks!

The Road to VIS 2024 - Reflections on Reviewing

The road to VIS 2024 is coming to an end and our work as OPCs is almost done. In a few short weeks, we will be opening the paper program at the conference and we will be saying farewell to outgoing OPC Tamara Munzner, who served the conference both last year as well as this one. Together with stalwart OPC assistant Petra Specht, Holger Theisel and Niklas Elmqvist will continue on for next year, and will be joined by Melanie Tory from Northeastern University as the third OPC.

In other words, this is as good a time as any to reflect on the road to VIS 2024: what went wrong, what went well, and what will happen in the future.

This is the tenth “Road to VIS 2024” post that we are posting to the IEEE VIS website. Overall, we count this blog post series as a positive achievement for VIS 2024. We hope that these posts have helped to shed some light on the inside workings of the conference for both early-career and senior researchers alike. We have valued the chance to speak to the community directly in this way.

If you cast your mind back to the early days of the blog, you may remember our second post on the “Call for Papers”, where we talked about the four changes we were making to the conference for 2024. Earlier this summer, we distributed a survey to our program committee to collect their feedback on these changes and the overall review process this year. Out of a total of 142 PC members and 12 Area Papers Chairs, we received 75 responses—thank you!—which we think is a pretty good rate, and certainly good enough to base our decision-making on.

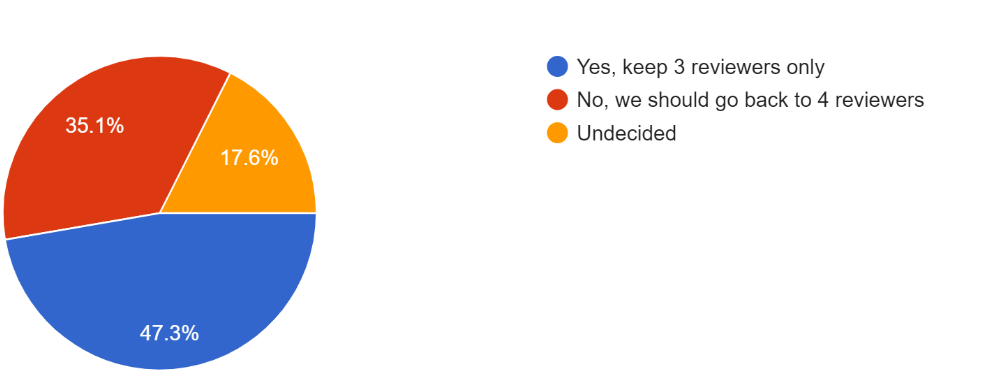

Our first change, to reduce the number of reviewers per paper from four to three (primary, secondary, and one external reviewer) yielded 47% in favor, 18% undecided, and 35% negative (see below). There were many free-form comments in favor and against; we read them all. Nevertheless, we think that this response warrants continuing the experiment for at least another year. We are awaiting the VSC’s final decision on this proposal for VIS 2025.

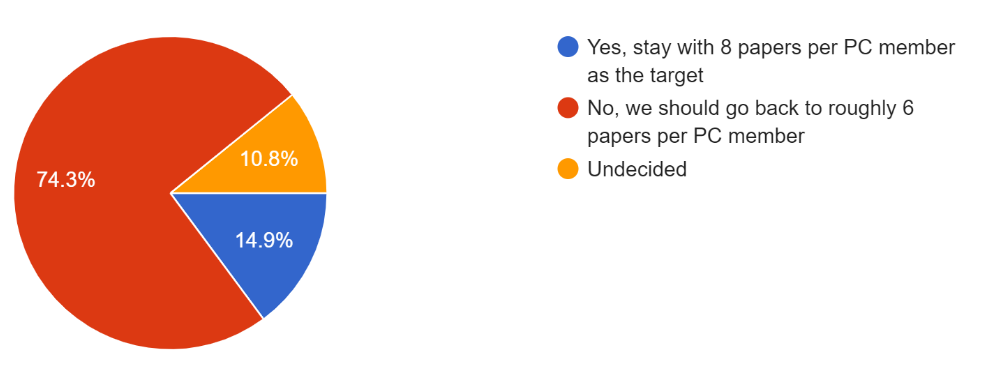

Our second change, to increase the load for each PC member from six to eight—and thereby reducing the size of the program committee to free up external reviewers—was much less popular. As can be seen in the pie chart below, 74% were against keeping this load and wanted to go back to 6 per PC member, 11% were undecided, and only 15% felt that the 8 papers per PC member load was acceptable. The comments were rather scathing, with some respondents saying they would decline the PC next year if the higher load was maintained for VIS 2025. While we note that 8 used to be the norm for the VIS conference in the past, we have heard this feedback loud and clear. We are awaiting the VSC’s approval on going back to 6 papers per PC member for VIS 2025.

We also collected general feedback on the review process and read each of the responses. Overall, PC members provided many helpful tips on managing the reviewing load, finding external reviewers, increasing the reviewer pool, improving the transparency of the process, and desk rejecting more liberally. We thank everyone who took the time to offer their thoughts on the process and we will be doing our best to incorporate their feedback, directly or indirectly, for next year.

This brings us to the topic of the future: VIS 2025. While we have not yet even held VIS 2024, it is never too early to prepare for what’s next. Beyond the changes discussed above—keeping three reviewers and going back to six papers per PC member—we have some bold ideas of where VIS should go. Some of these deal with improvements to PCS to reduce the impact of unethical reviewing; see our post on “Decisions”, for more details on this. However, some ideas that we are considering are sufficiently bold or experimental that we would first like to hear what the community has to say about them. For this reason, the VIS 2024 and the incoming 2025 OPCs plan to discuss them at the VIS town hall during the conference. To give you a flavor of some of the things we are considering, we’re thinking about (1) extending the deadline a week for only supplemental material, (2) giving authors the option to publish anonymized reviews with their accepted papers, and (3) introducing a student reviewer program where primary reviewers optionally get to invite a Ph.D. or masters student as an advisory “student reviewer” for each paper they manage.

We hope that you will join us at the VIS 2024 town hall so that you can weigh in on these ideas, and offer any other ideas that you may have for improving VIS in the future.

Anyway, our work here is almost done. This has been quite a ride and we’re looking forward to a vibrant finale at the conference. We can’t wait to let you see the exciting scientific program that the community has assembled. See you in St. Pete Beach!

VIS 2024 - State of Open Practices Report

At VIS last year, we in the Open Practices Committee led a town hall where we discussed the long-term Open Science goals for our community. These were:

- Research should be accessible to everyone. Financial means and privileged access should not limit anyone’s ability to participate in and learn from visualization research.

- Research should be transparent, scrutinizable, and trustworthy. Authors should be as transparent as possible about their research processes and results. Increased transparency can help reviewers and readers judge for themselves whether the research conducted was plausible and whether the results are reliable.

- Research should be replicable and/or transferable. We believe that our community should support knowledge transfer between teams and that research results should stand up to scrutiny by future researchers.

For VIS 2024, we set objectives to further encourage our community to submit supplemental materials for review. We provided guidelines to assist in the submission of supplemental materials as well as guidelines for reviewing these materials. We have also continued to encourage authors to post preprints on approved servers and to provide clearer guidance for the community through the VIS 2024 Open Practices pages. To further increase our transparency, we provided an updated VGTC journal template allowing the sections “Supplemental Material”, “Figure Credits” and “Acknowledgements” on the reference-only pages.

Accepted authors (congratulations, by the way!) may also have noticed some additional questions in the camera-ready submission form, asking for information about their open practices for their work in terms of posting preprints, preregistration, and supplemental material. As our community continues to move towards more Open Science, we also asked accepted authors to reflect and consider if their work exhibited exemplary or noteworthy practices around documentation, reproducibility, or transparency. Thank you to those of you who provided all of this extra information.

So, what is the state of Open Practices for VIS 2024? How do we compare to last year, and what more can we do in the coming years?

Full Papers

Let’s have a look first at the full papers. Of the 124 accepted full papers to VIS 2024, authors reported the following Open Science practices:

Preprints

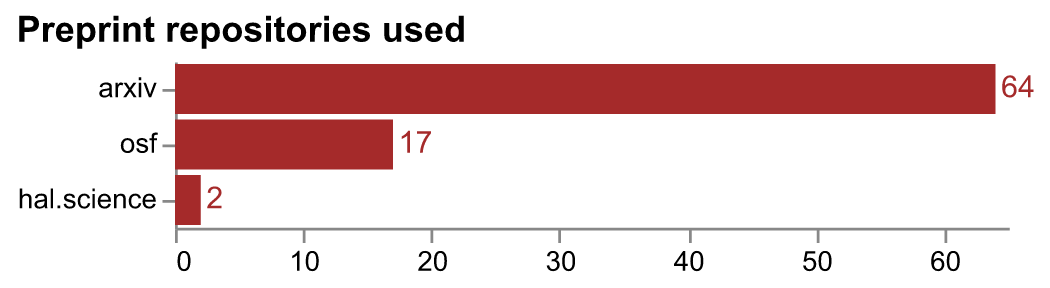

For VIS 2023, we asked authors about preprints. Self-reported data showed that about half of accepted authors posted their preprints on arXiv, just over 6% to OSF, 8% to another source, and around 35% not at all. How does this year compare?

This year, we see a slight improvement in the posting of preprints, up to 83 (67%) of submissions. This is a 2% improvement over last year. Furthermore, we see that all reported preprints have been posted to a free and open repository (ArXiv, OSF, or HAL). This is a step in the right direction.

Open Practices recommends uploading a preprint of your work to a free and open-access repository to make it more findable and accessible. Our Open Access Preprint Guide and FAQ provides more information and several tutorials to help make your preprint more available. It is never too late to do this!

Supplemental material

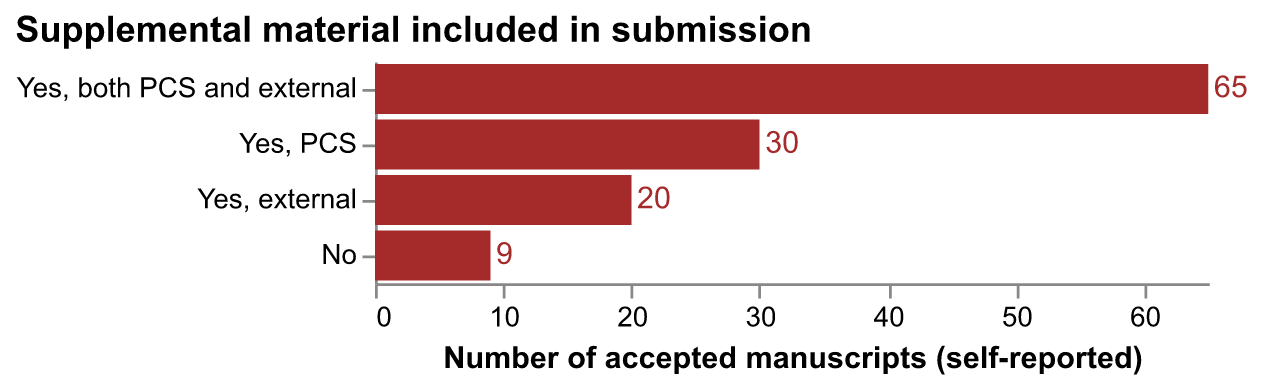

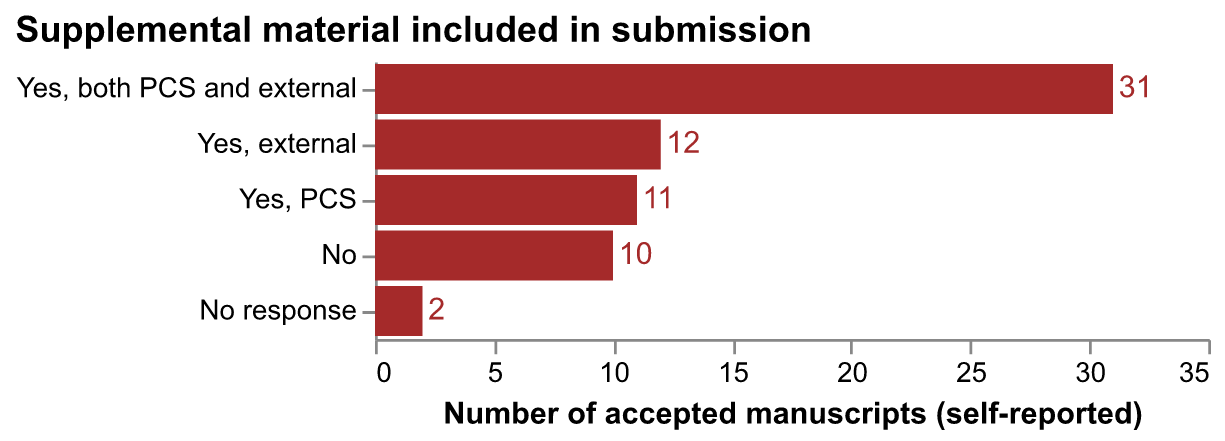

115 (93%) of accepted submissions used at least one supplemental material field, whether PCS, external, or both PCS and through an external link.

While not all papers necessarily have relevant supplemental material (for instance, position papers), for nearly all paper contributions, having supplemental material (like experimental data, code bases, or even just additional proofs and analyses) helps the work to be scrutinizable, so we view this high percentage as a step in the right direction. We do, however, recommend uploads to both (1) PCS for review as well as (2) a free, reliable, and long-term archive, in alignment with VIS’s long-term Open Science goals. This redundancy allows both a static copy of record associated with the entry in the IEEE digital library, as well as an open and more easily scrutinized or re-analyzed version of the work.

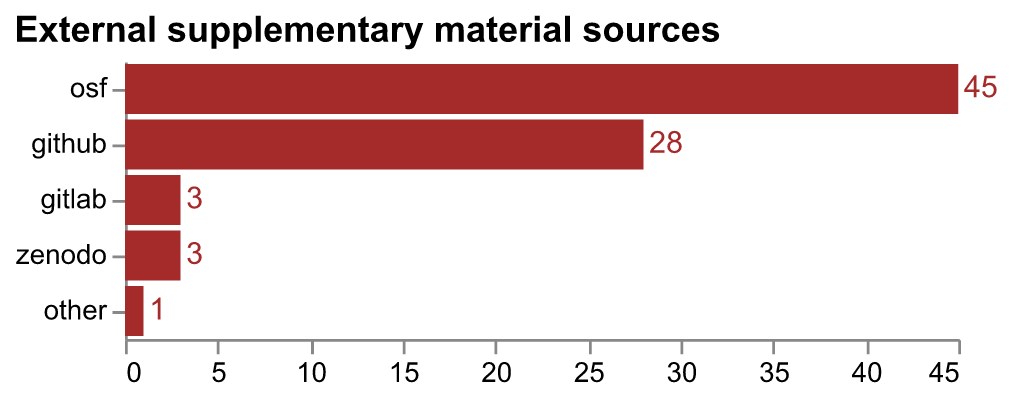

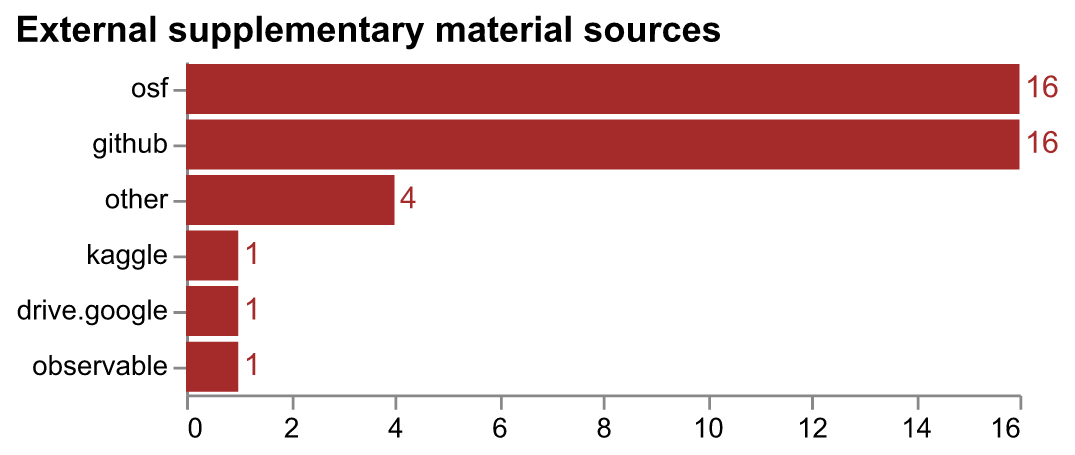

Besides PCS, where did accepted submissions upload their supplementary material?

We see that 80 (around 65%) of accepted submissions uploaded their supplementary materials to an external source in addition to or instead of PCS, with the majority using OSF. For further guidance on where supplementary material should be upload, please see our FAQ: Where should I upload supplementary material?

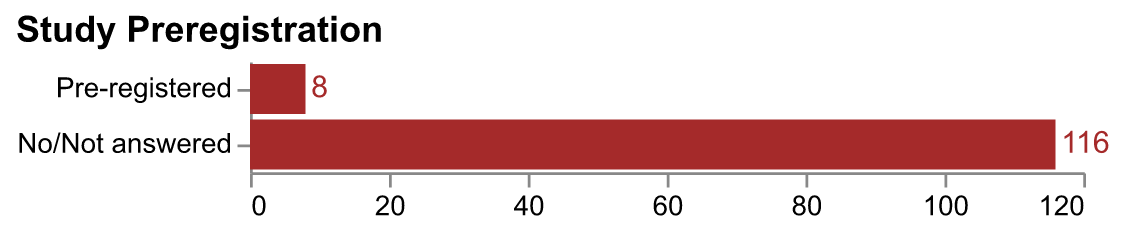

Preregistration

We also asked about study preregistration, another new question for this year. Only eight (12.5%) submissions out of the 124 full papers reported preregistration of their studies, seven of which did so on OSF Registries and one on AsPredicted.

This is a clear area where our community has room to improve. VIS Open Practices still needs formal recommendations for study preregistration, and we acknowledge that this may not be less relevant for certain contributions. However, for work involving empirical studies, preregistering an analysis plan helps us as researchers to clearly separate hypothesis generation (postdiction) from hypothesis confirmation (prediction), thus leveraging the benefits and maintaining awareness of the limitations of statistical inference while improving the study’s reproducibility and replicability [1]. OSF provides an excellent set of resources for preregistering your project. For future iterations of VIS, the Open Practices committee plans to examine more deeply where and how we support the community in preregistering relevant studies. We look forward to conversations and feedback on this process with all of you.

Short Papers

Now, how does the short papers track look? Of the 66 accepted short papers, authors reported the following on Open Practices:

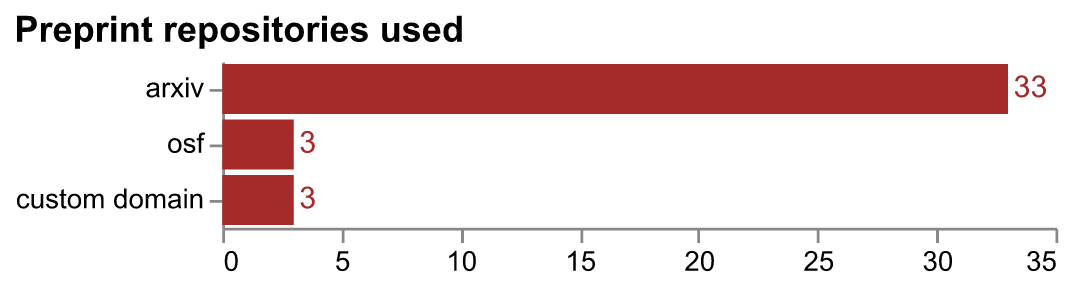

Preprints

39, or around 59% of accepted short papers, posted a preprint of their work. This is lower than what we see in the full paper submissions and we would like to see this number improve in the coming years.

Of those submissions that posted preprints, most used ArXiv, a few OSF, and a few used custom domains, mainly their university hosting services.

Supplementary material

Of the 66 accepted short papers, 54 (around 82%) included supplementary material in some form in their submission, whether through PCS directly and/or through upload to an external repository. The majority of authors, as we can see, did both.

And where did authors upload their supplementary material externally?

Here, we see more variation than for the full paper submission. GitHub and OSF are similarly used, and some authors also used Kaggle, Google Drive, and Observable to host their supplementary material. As for the full papers, we recommend archiving supplementary materials to a free, reliable, long-term archive—GitHub links can change or disappear.

Self-nomination for exemplary open practices at VIS 2024

Finally, we asked accepted authors to consider self-nominating if they feel their practices around documentation, reproducibility, and/or transparency are noteworthy.

Of the 190 accepted submissions across both full and short paper tracks, 37 self-nominated their work for exemplary open practices. This is further split between 27 for the full paper and 10 for the short paper track.

Most self-nominations, whether full or short paper track, indicated provision of code, data, thorough documentation, and/or other study instruments (e.g., cleaned transcripts, codebook, study protocols) for reproducibility and/or replicability. Several also noted study preregistration and registering materials under Creative Commons licenses for re-use. As a community, we hope that soon, such practices will become the norm for all submissions.

We are grateful to those authors who self-nominated and provided further details on their practices. We are still discussing how to move forward with this information and plan to reach out to some or all self-nominees in the coming months for thoughts and feedback.

Thank you, authors!

Thanks again to all authors who provided this information. We are grateful for your time and contributions and look forward to ways that we as a community can (and should!) continue to make our science more transparent and scrutinized. As always, we welcome thoughts and feedback from the community and look forward to seeing you in Florida in just over one month.

References

[1] Nosek, B. A., Ebersole, C. R., DeHaven, A. C., & Mellor, D. T. (2018). The preregistration revolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(11), 2600-2606.

The Road to VIS 2024 - Decisions

With the final acceptance decisions behind us, the official VIS 2024 review process is coming to a close. We felt that it was worth taking a moment now to look back at this most recent milestone in the review process: the decision making. In fact, doing so can be quite educational; not so much for the vast majority of papers where the process went right, but rather for the very few where it went wrong (even very wrong).

Because IEEE VIS publishes its papers in a special issue of the IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics (TVCG) journal, the VIS review process has real teeth. TVCG stipulates two full review rounds: an initial review round (starting April 1) followed by a second round for minor revisions (starting July 1). Papers that proceed to the second round are said to be “conditionally accepted”, but make no mistake: the second round is a real review round. The primary reviewer, after discussing with the full review panel, is supposed to list required revisions in the first round review. To address these, authors get almost a full month, which is consistent with TVCG (3 months for major revisions, 1 month for minor). If these required revisions are not addressed to the satisfaction of the primary reviewer, we have no qualms about rejecting conditionally accepted papers in the second round.

For VIS 2024, we conditionally accepted a total of 129 papers out of 557 submitted papers in the first round, yielding a provisional acceptance rate of 23.2%. Even if there is no explicit target acceptance rate, this is a low number; for comparison, it was 25.8% in 2023. While we regret the low rate, our decision-making was strictly based on scientific merit and not pursuit of an arbitrary acceptance rate. Following the process outlined in our last blog post on “From Reviews to Decisions”, the conditional accepts were determined through careful discussions between the reviewers, PC members, APCs, and OPCs. We shared the first-round notifications on June 6, 2024. Beyond the 129 conditional accepts, we also recommended an additional 29 as “TVCG fast-track”; submissions that showed promise but which we deemed would need a major revision requiring more than a brief month to bring over the finish line.

What followed in that interim of three weeks in June was no doubt feverish activity across visualization labs all over the world as authors of conditionally accepted papers raced to address all the required revisions. On July 1, all 129 papers were resubmitted to the second round. At this point, the second round reviewing commenced, with the primaries (and sometimes secondaries) checking each paper, then the APCs, and finally the OPCs.

That process ended earlier this summer, and we are happy to say that the majority of authors really did do their due diligence by carefully addressing all the required revisions. A total of 124 of the 129 papers that were conditionally accepted from the first round were finally accepted at the end of the second round. For a small number of these 124 papers, there were minor issues that the OPCs, APCs, and program committee members flagged and discussed. In the end, all of these issues could be handled within the confines of the regular review process. Congratulations to the authors of these 124 papers—we very much look forward to seeing your work being presented in Florida this October!

But what about the remaining 5 papers that were rejected in the second round? We feel there are valuable lessons here to share with the community while keeping the narrative high-level enough to protect the identities of the authors, reviewers, and PC members involved.

For one of the five rejected papers, the primary flagged a situation where the authors had failed to address a critical requirement: framing the novelty of the contributions of their work with respect to previous work. Moreover, they removed almost 20 references in their second round revision. When looking closer, we found that the authors had addressed a comment about reorganizing the related work by shrinking it in half and cutting many of the original references. Importantly, several of the missing relevant literature that the reviewers asked the paper to cite had not been added to the new version of the paper (even if the authors claimed they had done so in their revision report). We OPCs ended up spending a significant amount of time checking that this was not just a case of the authors trimming the fat off the paper, but came to the same conclusion as the primary. The changes to the related work did not sufficiently address the required revision. The paper was rejected.

For a second rejected paper, the new revision was submitted to the second review round with exactly 10 pages of content and 2 pages of references. As VIS authors will know, we only allow papers with up to 9 pages of content and up to 2 pages of references. Nevertheless, the authors—some senior ones among them—resubmitted the paper with a full page beyond the limit. The paper was rejected.

You might argue for both of the above cases that these are situations where the OPCs could have engaged the author team in a conversation to address the issues rather than rejecting outright. Unfortunately, there simply isn’t sufficient time in the schedule for authors to shrink their paper down by a full page, or address novelty concerns that were not handled during revisions. And besides, there is a fairness issue; why should some authors get special treatment? What if everyone did this?

The final three rejected papers share a common theme: a severe conflict of interest violation. During the final checks on the list of accepted papers, it was discovered that a paper had been managed by a primary reviewer who was the former Ph.D. student of the paper’s senior author. As we dug deeper, we found two more conditionally accepted papers involving that senior author that had been handled by the same primary reviewer (a member of the IEEE VIS 2024 program committee).

Your own masters, Ph.D., and postdoc advisors are permanent conflicts in the IEEE VIS community (and in most scientific communities). This means that unlike for your paper co-authors or grant co-investigators, where conflicts disappear after three years, your conflict of interest with your former advisor (and, inversely, with your former students) never goes away. This information is widely known in the VIS community; it is enshrined in our paper submission guidelines with a link to the IEEE VGTC Ethics Guidelines, and it was recently discussed in our Road to VIS 2024 blog post on “Handling Conflicts”. We tell all our PC members to be mindful of conflicts, both when they are recruited as well as when they bid on papers and recruit reviewers.

In other words, knowingly reviewing papers written by your own Ph.D. advisor is a very serious breach of the integrity of the IEEE VIS review process.

PC members see the identity of all authors in PCS (our submission reviewing system) even if a paper is anonymized. This particular primary reviewer had been given clear instructions, did not declare a conflict with their advisor, and failed to tell us that they had been assigned three of their advisor’s papers as primary reviewer—for four months!

As far as we can tell, nothing like this has ever happened before in the 30-year history of the VIS conference. We thus had no procedures or tool support to spot this specific problem. Furthermore, with a total of more than 1,900 unique authors submitting papers to VIS 2024, it is virtually impossible for the OPCs and APCs to be fully aware of all conflicts between them. Instead, we rely on our PC members, reviewers, and authors to carefully self-declare all these conflicts in advance of the review assignment process. Note that we don’t expect perfection: after the assignments are released, there is a chance for reviewers to let us know if a previously undetected conflict appears. There were several situations when this happened, causing us OPCs to swap papers between PC members when people discovered a conflict not previously declared.

Unfortunately, the fact that this conflict did happen irrevocably compromised the review process for all three of these papers. Primary reviewers have a significant impact on a paper’s fate by leading the discussion and summarizing the other reviews. There is no easy way to disentangle this impact. Perhaps if the problem had been spotted in the first round, we could conceivably have replaced the primary. At this point, near the very end, it is impossible to know whether these papers would have even made it to the second round with an unconflicted primary. There is also no time to run the review process all over again given our tight schedule. As a result, all three papers were rejected, but with a special offer from TVCG for the papers to be immediately resubmitted to the journal while retaining the two unconflicted reviewers and only replacing the primary.

The fallout from this incident is significant. Most serious is the impact on the graduate students whose papers were rejected due to factors beyond their own control. Second, the senior author (the Ph.D. advisor of the primary reviewer at fault) has three of their conditionally accepted papers rejected, again due to no fault of their own. And third, the primary reviewer who committed this breach of review integrity and professional ethics has opened themselves up to an academic misconduct investigation.

The greater lesson from this incident is to take conflicts of interest very seriously. Make sure that you carefully declare not only your co-authors and co-investigators in PCS, but also your masters, Ph.D., and postdoc advisors. If you have ever advised students, you should also declare your own current and former students as permanent conflicts! Vigilance about your own conflicts is one good strategy to protect yourself from situations like this in the future.

There is damage to the VIS review process as well. Our goal when addressing the incident was to protect the scientific integrity of VIS (and TVCG), but there can be no perfect solution to this kind of difficult problem. We OPCs and APCs will be reviewing our procedures to ensure that this problem will not happen again. We will be looking into ways to improve the PCS paper submission and reviewing system to spot problems of this nature. And we will do our best to educate the community about the importance of conflicts. This blog post is part of that latter effort.

VIS Community Opinions on Hybrid Event Formats

In a post by the VIS Executive Committee (VEC) earlier this year, we introduced our initiative to determine the extent to which VIS should assume a hybrid format, so as to broaden participation while ensuring positive experiences for both in-person and remote attendees. As part of this initiative, we partnered with members of the IEEE Visualization and Computer Graphics Technical Community Executive Committee (VGTC ExCom) to conduct an online survey to take the pulse of the community, to collect data regarding conference attendance patterns and preferences, to determine the sentiment toward potential hybrid experiences, and to collect ideas. In this post, we summarize the results of this survey.

Since January, 192 people responded to our call to participate in the survey, which we disseminated via community mailing lists and social media. 138 respondents selected VIS as their primary VGTC conference; our analysis focused on this subset of responses. We believe that the VIS community is reflected in the survey responses, which span the dimensions of world region, gender, level of education, age, affiliation, and VIS attendance history. However, some voices are either over- or under-represented when we compare the demographics of survey respondents to VIS attendance data; for instance, VIS attendees from North America are slightly over-represented, while those from Oceania are under-represented.

Reflection on Prior Conference Experiences

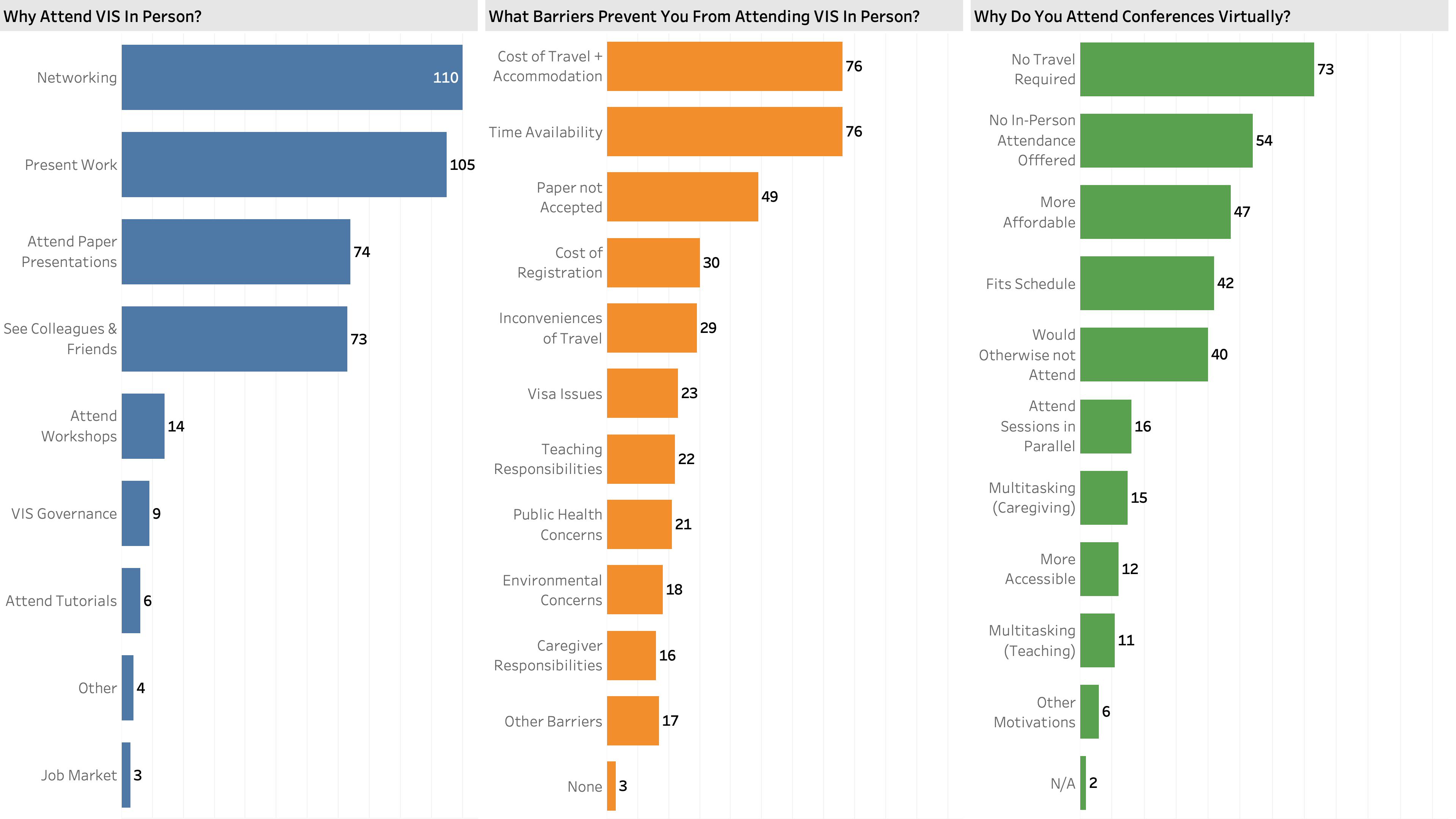

In the first half of the survey, we asked about recent conference experiences, including the motivations for attending either in person or virtually, as well as the barriers that prevent people from attending a conference in person. The results are shown in Figure 1. For each question, respondents could select up to three considerations, which included an ‘Other’ option that allowed them to specify their own. Highlights include:

Figure 1: Community responses to three questions from an online survey regarding IEEE VGTC conferences, filtered to the subset respondents who identified IEEE VIS as their primary VGTC conference (N = 138). For each question, respondents could select up to three considerations, which included an ‘Other’ option that allowed them to specify their own.

- Top three motivations to attend VIS in-person: (1) networking, (2) present work, (3) attend paper presentations.

- Top three barriers to attending VIS in-person: (1) cost of travel and accommodation, (2) time availability, (3) paper not accepted.

- Top three motivations to attend conferences virtually: (1) no travel required, (2) no in-person attendance option offered, (3) affordability.

The open-ended comments largely corroborate what we saw in the fixed-response questions, however we also noted a recurring desire for hybrid formats to ensure accessibility. Additionally, respondents indicated how environmental concerns also influence their attendance decisions, with some choosing not to fly or combining travel with personal time to mitigate environmental impact. Finally, several respondents mentioned significant personal safety and human rights concerns associated with potential conference locations.

Next, we asked about respondents’ preferences and behaviors when attending conferences virtually. The majority of respondents reported consuming less than 50% of the conference program content, preferred livestreaming some of the content and watching the rest asynchronously. The majority preferred interacting with speakers via a basic chat interface, Slack or Discord, or a web application like sli.do. They preferred interacting with other attendees via Slack or Discord, a basic chat interface, or asynchronously via email. In the open-ended comments, we noted a particular appreciation for the Discord instance associated with VIS 2022, although the effectiveness of such a platform depends on activity levels.

Opinions on Future Conferences

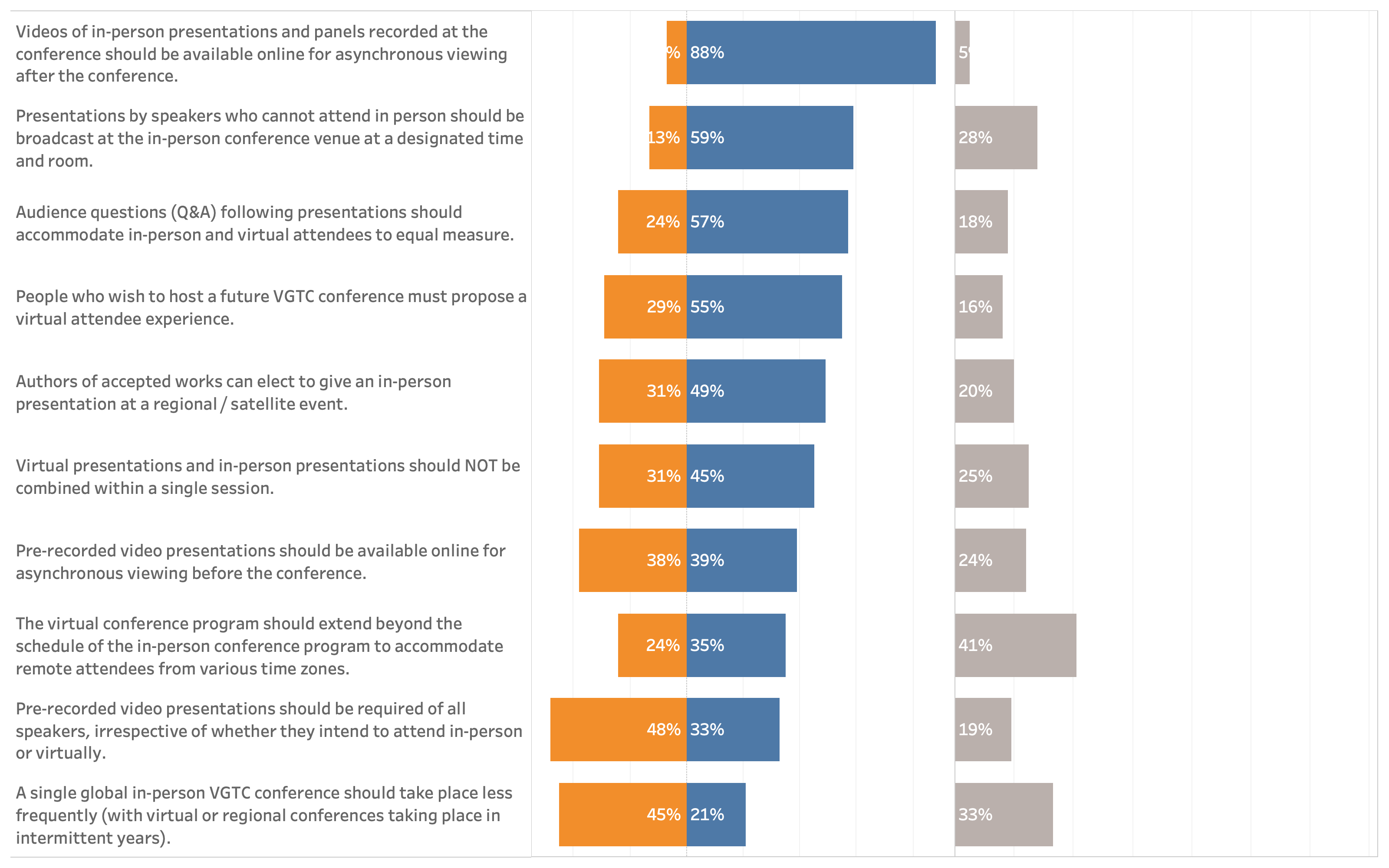

In the second half of the survey, we asked respondents for their opinions and preferences with respect to future conferences. In particular, we asked participants to either to agree or disagree with a series of statements regarding the specifics of possible hybrid conference arrangements (See Figure 2), which included statements about presentation video recorded before the conference, presenting at satellite events, and the integration of in-person and virtual presentations.

Figure 2: Percentage of survey responses (N = 138) that Disagree or Agree with the statements regarding future VIS conferences listed in the left column, along with the percentage of Neutral responses.

So what do respondents largely agree on? Most respondents (88%) want video recordings of in-person presentations and panels to be made available after the conference (7% opposed, 5% neutral). The majority (59%) agree that presentations by speakers who cannot attend in person should be broadcast at the in-person conference venue at a designated time and room (13% opposed, 28% neutral). Similarly, the majority (57%) agree that Q&A following presentations should accommodate in-person and virtual attendees to equal measure (24% opposed, 18% neutral). Finally, the majority of respondents (55%) agree that those who wish to host a future VIS conference must propose a virtual attendee experience (29% opposed, 16% neutral). The open-ended comments largely support these preferences, with calls for standardizing presentation formats across sessions and using familiar remote communication technology.

There was no clear majority opinion for other questions that we posed, though if we consider the percentage of neutral responses, we should avoid requiring pre-recorded presentations from speakers who elect to present in-person, and we should not consider changing the annual cadence of an in-person VIS conference.

Unsurprisingly, nearly half of the respondents said “it depends” when asked if they will opt to attend future VIS conferences remotely; less than 10% said they would attend virtually for most / all conferences that offered such a format, with about the same percentage saying they do not plan to attend future conferences virtually. The majority of respondents indicated that the virtual registration fee should be 25% or less than the full in-person registration fee. If attending virtually, the majority of respondents indicated that they would livestream keynote sessions but opt to watch paper talks asynchronously. This preference is also reflected in CHI 2024 organizers’ decision not to provide a synchronous conference experience for remote attendees, or as they put it: “Live is Synchronous, Remote is Asynchronous”.

Opinions on Satellite Events

Finally, relative to remote participation in general, we noted less enthusiasm or willingness to attend satellite conference events. The comments suggest that the quality of satellite events depends heavily on attendance and local organization strength, and that the attendance of a satellite event is contingent on the number and presence of local paper presenters. However, European satellite events are particularly attractive relative to others due to Europe’s developed rail travel network, particularly when the VIS conference takes place outside of Europe.

Panel at IEEE VIS 2024 on VIS Conference Futures: Community Opinions on Recent Experiences, Challenges, and Opportunities for Hybrid Event Formats

We will host a hybrid panel dedicated to discussing the implications of the data summarized above, gathering together the diverse perspectives that will further contextualize and reflect the voices from our survey. Given the range of responses and the strong opinions that respondents voiced in the open-ended comments, we expect this to be a lively forum that will inform and inspire VIS community members and especially those in organizing committee roles (or who may undertake such roles in the coming years). This panel serves as a platform to address the complex and interconnected issues surrounding the future of VIS conferences, particularly with respect to those where community members have differing opinions, as well as to complement the perspectives that came across in the survey results. As we navigate the landscape of hybrid event formats, it is essential to gather diverse perspectives from the VIS community, to better inform decision makers in organizational roles so they they can ensure that VIS remains inclusive, engaging, and impactful.

We will begin by briefly summarizing the VIS attendance data and survey results. Next, we will ask the panelists to remark upon their own vision for future VIS conferences, as well as their opinion on what is unique about hybrid experiences for VIS relative to other conferences. We will then anchor the discussion around questions for which there is little agreement within the community (See Figure 2 above). To ensure that the panelists are well-prepared for the panel, we have provided them with access to interactive dashboards containing survey results; these dashboards have affordances to filter and facet results by different demographic segments.

Our panelists represent different cross-sections of our community, with perspectives spanning career level, region, gender, and affiliation. In keeping with the theme of the panel, some panelists will appear in person, while others will join remotely.

Our panelists include: Tim Dwyer, John Alexis Guerra-Gómez, Petra Isenberg, Takayuki Itoh, Elsie Lee-Robbins, and Andrew McNutt; the panel will be moderated by Matthew Brehmer and Narges Mahyar.